June 2 – 8, 1944

Friday, June 2

We advance up the Appian Way highway south of Rome. We were walking up the road single file when I noticed an American chaplain approaching in a jeep. The jeep driver let him out near me, and he walked along and talked with us for a while. He said that this road was the road that the Apostle Paul walked on when he went to Rome. I was very impressed. After a while, the chaplain motioned for his jeep driver, and he rode up a ways and got out and walked and talked with the soldiers there as they walked along.

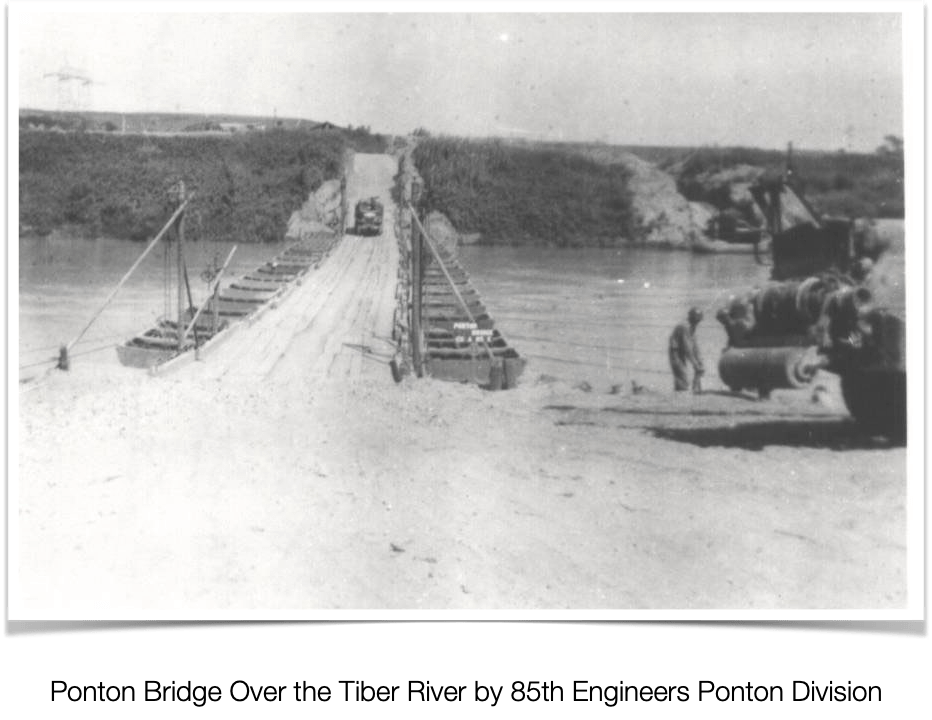

Later in the day we came to the Tiber River in Rome and had to wait several hours while our engineers built a pontoon1 bridge across the river. The Germans had destroyed the bridges before we got there.2 After crossing the Tiber River, we continued advancing north through Rome. In the evening we went into a large vineyard and were told to dig in. I proceeded to dig a prone shelter laying the dirt on the enemy side of the hole.

Apparently, the Germans saw us go into the vineyard as very soon German artillery and mortar shells began to fall in the vineyard. I got into my prone shelter and lay as low as I could. Some shells landed close to me, but I wasn’t hit. Our Sergeant Hoziah was killed here as a shell landed on his foxhole. His foxhole was about 15 feet from me. The field medics came up and carried Sergeant Hoziah out.

Later at mail call, I received several letters from Nettie, and a watch with a radium dial. I had asked for one so I could tell time at night. Nettie wrote me a letter every day except a few days when Terry was born or when I was home.

Saturday, June 3

I rode on a tank in Rome most of the day. Six soldiers were on the tank, and we were to dismount and give support in the fight and protect the tank from grenades and other weapons close by if we came under fire. We moved slowly not knowing if the Germans were still there. I do not know the names of the streets we were on, but some of them appeared to be back streets. On one of the back streets, a building had been damaged and several kegs (probably wine) were exposed. We did not stop.

We came by the old Roman coliseum [Colosseum] ruins and several other large old buildings.3 Most of the buildings were made of stone, but some of the buildings were in a decayed state, but this part of Rome didn’t appear to have much war damage. The Germans did not fight for the city of Rome.4 They went on up above Rome and prepared defensive positions there. They often dug or had Italian labor dig slanted slots in the road bank. They could not be seen in the slanted slots there as we approached, but they could pop out firing and surprise us. We always had scouts (point men) go ahead of us to detect ambushes before we walked into them.

We also came by the street that led to the Vatican, but I did not see anyone. It began to appear that the Germans had left Rome, so in the evening we gathered in a field and had a church service. The Catholic service was on one hill, and the Protestant service was on another nearby hill. We spent the night there but did not dig in. We lay on the ground, and I used my helmet as a pillow.

Sunday, June 4

We walk and ride all day trying to catch up with the Germans. Several American trucks were used. The trucks would pick up a load of soldiers, advance about 15 or 20 miles, unload the soldiers, and go back and pick up another load of soldiers. We kept walking, and with the truck leapfrog and walking, we must have advanced 45 or 50 miles this day.

We began to see prepared German defensive positions along the side of the road, probably made by Italian labor, and we began to hear artillery and German machine gun fire up ahead as our forward troops made contact with the Germans. We left the road and advanced slowly in the country-side. Some artillery and mortar fire began to fall where we were, and as we advanced, machine gun fire began to be heard up ahead. We advanced slowly as our forward elements engaged the German troops. We were in back of the fighting, so we advanced slowly single file. Once a shell landed between two men up ahead of me in the single file. They both went down, but I don’t know how bad they were hurt. The field medics came and carried both of them back. The sergeant sent word back for us to “close it up,” so we moved up to close the gap left when the men got hit.

Our forward units were in contact with the Germans the rest of the day and night. An American machine gun near me kept up continuous bursts of fire all night, and we had incoming mortar and artillery fire all night. I did not get to sleep any except short naps when we were stopped. Once, while we were advancing slowly single file about half asleep, some distance behind me in the line two German soldiers grabbed one of our guys and disappeared with him in the confusion. We were in contact with the Jerries most of the night.

Monday, June 5

In the morning, we found that the Germans had pulled back to another defensive position several miles up the road, so we walked almost all day in an effort to catch up with the Jerries.5 We walked at a fast pace for fifty minutes and rested ten minutes. About 11 am, we came into a field where many of our troops were gathered. It appeared that most, if not all, of our 133rd Regiment was there. After everyone got there, our officers gathered near the colonel or general (I was so far back I could not tell which). He gave us, mostly to the officers, a talk impressing on us the necessity to keep putting pressure on the Germans. After about an hour, the meeting broke up and our company began walking up the road again.

Over in the afternoon, I began to hear machine gun fire and could tell that our forward units had made contact with the Germans. I was very tired and began to feel ill, and was having trouble keeping up with my unit. I would fall behind some during the fifty minutes and had to catch up in the ten minute rest period. I had never failed before to keep up with my unit, even in basic training. Our sergeant noticed that I was having trouble. I told him that I was feeling sick. He had me trade weapons with one of the M1 riflemen. The BAR weighed 21 pounds, and an M1 rifle weighed 9 pounds. This helped some, and when we stopped for the evening we traded our weapons back.

Shortly after dark, my company came to a wheat field and we were told we would spend the night there. The wheat had been cut and placed in shocks of bundles of wheat like they did in America. I found a shock of wheat and burrowed into it, and went to sleep laying on my aching stomach. My legs and rear end were outside the shock of wheat. In the night, it felt that my legs and rear end were wet. “It must have rained,” I thought and went back to sleep.

Tuesday, June 6

In the morning before dawn, I felt so wet and uncomfortable that I got up and found that I had a bad case of the Gl’s (diarrhea), and had messed up my clothes very bad. The rest of the soldiers had not gotten up yet. What to do? We would be moving out soon to continue chasing the Germans, and there was no sick call.

At one side of the field, it appeared that there might be a stream, so I went down there. There was a spring and stream with running water. I took off my pants and underwear and attempted to clean myself up as best I could. I threw my underwear away. I did not have any other underwear. I had thrown away my blanket, field pack, and gas mask long ago to lighten my load. I tried to wash my pants in the cold water of the stream. I put my wet pants back on even though they smelled very bad. While I was cleaning up, an Italian man came through the reeds and looked at me. He did not say anything, but I moved away from the spring. I am sure he was watching to see if I was doing something to the spring.

When I got back to the company, I learned that the invasion had started in France. We were very happy, and most felt that now our fighting would not be so severe. We were wrong. For several days now we had been attacking and trying to catch up to the Germans when they ran. I learned later that we had orders to attack and tie down as many German soldiers as we could to keep them from being sent to fight our invasion force in France.

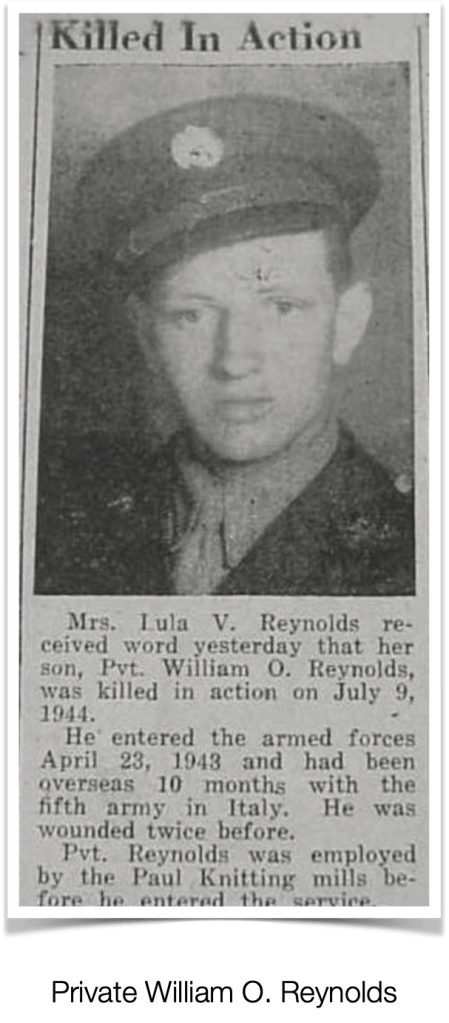

Back at the company area, we were issued water and three boxes of K-rations, and again began walking to catch up with the Germans. My assistant gunner reported that he would be walking far behind me because I smelled so bad. We would walk 50 minutes and rest 10. I felt better, but I was weak and had some trouble keeping up, but fortunately, in the afternoon, 6 members of my squad, including Reynolds, Bill Friedlander and I, were ordered to ride on a tank. We were beginning to make contact with the Germans, and it was our job to support the attack and to give protection to the tank from hand grenades and other close weapons when we came under fire. The tank did soon come under fire, and we dismounted when the tank began to fire back. We took such cover as was available and fired our weapons some toward the German lines. I did not see any of the enemy as they were firing from foxholes and prepared positions. After a while, the firing stopped. The Germans did not attempt to blow up the tank. We remounted the tank when it quit firing. Our soldiers captured three German soldiers, and they were taken back to our rear area.

At dark, the tank stopped and we dismounted. I attempted to get some sleep on the ground using my helmet as a pillow. Also, we were receiving some incoming mortar fire. Our machine guns on both sides of me kept firing bursts all night toward the German lines. We were twice ordered to remount the tank as it changed positions. I was still not hungry, but I ate some of the K-ration crackers and some German wafers that I had found in a German foxhole.

Wednesday, June 7

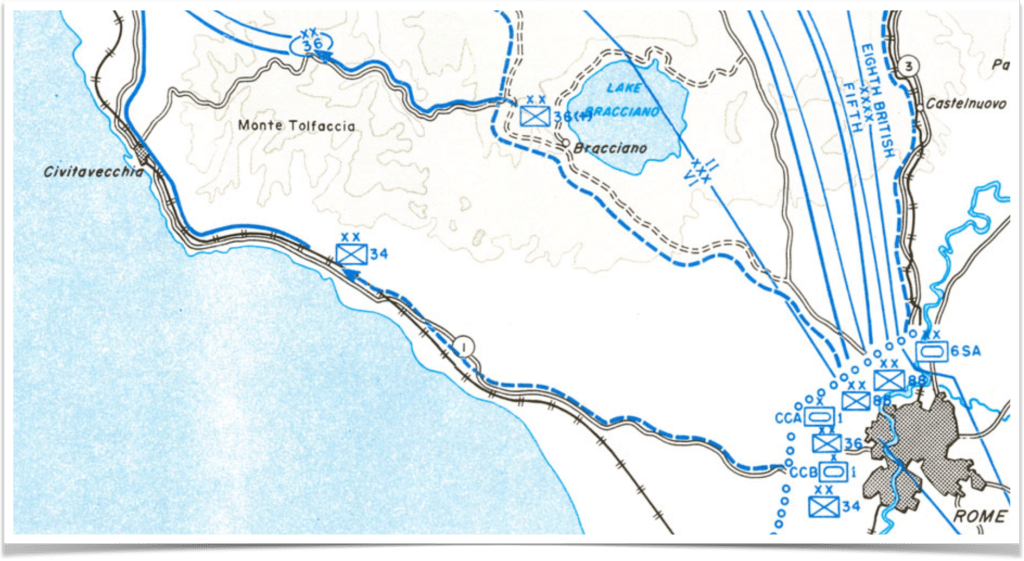

We were probably 60 or 70 miles north of Rome by this time.6 This morning it appeared that the Germans had fallen back to another prepared defensive position. The tank (with us on it) and our other forces move forward, but we were receiving some incoming German artillery and mortar fire. We moved on slowly, but the artillery and mortar fire became heavier. When our tank began firing, we dismounted and followed along with the tank. When incoming artillery and mortar fire came in, we lay on the ground as low as we could get. In the afternoon, we began to receive some rifle and machine gun fire along with the heavy stuff. By this, I knew we were getting close to their defensive position.

When it became dark, our tank pulled alongside a long tile block building and we dismounted. The building was long, like a chicken house. Incoming artillery and mortar fire fell around us most of the night, and our forces returned artillery and mortar fire. When the tank stopped, I took cover by laying on the ground, near the tank, against the building, but I left my BAR on the tank. I did not get much sleep.

Thursday, June 8

When it began to get daylight, we went back to the tank and I found that a shell had hit the wall beside the tank during the night, and my BAR was covered with dirt, brick dust, and pieces of brick. It did not appear to be damaged, so I cleaned it the best I could, but I was afraid to disassemble it as we were close to the Germans. I was hoping it would fire when I needed it.

We were issued some water and K-rations. After a few minutes, I noticed that the tank commander was talking on his radio. I don’t know what was said, but soon he hung up and told us, “OK men, mount up. We are the point today.” Being point, or the scout, meant that our tank, with those riding on it, was going to lead the attack.

Our tank, with six of us on it, began to move toward the German lines. No other tanks or soldiers were with us, and no one was firing. We were the point, and the others would come up when we made contact with the enemy. After we had gone out a few yards, I noticed in the distance a horse and rider rapidly approaching our tank from the rear. We watched the rider approach, and Reynolds said, “Cox, do you think they are attacking us on horseback?” Before I could speak, Bill Friedlander said, “I think the rider wants to tell us something.” The tank stopped as the rider got closer, and the rider was saying, “Tedisky, Tedisky,” and was pointing frantically toward the German lines.7 Our tank commander smiled and waved saying, “Thank you Pizon [Paisan], we will get them,” and we continued to move toward the German lines.

We continued to advance and went under a large power line with several lines and metal tower posts anchored in cement like many lines in the states, and several yards away there was a canal in front of us. I saw a German soldier run across the bank of the canal on our right and disappear into his foxhole.

There was no firing, but our tank stopped and we dismounted. As we were moving behind the tank, a German machine gun opened up spraying the tank and us with bullets. I felt a hard smash in my upper abdomen on my left side as German machine gun bullets hit me and spun me around behind the tank. And as the bullets propelled me forward, I was able to keep my balance. The bullets shredded my left side, and my side felt very heavy, but the bullets didn’t put me down.

The tank began to move toward the machine gun, and we went with it firing our weapons around the tank. Bill Friedlander noticed that I was getting bloody and could hardly stand. “Where are you hit, Cox?” “In the belly,” I replied. I did not know what to do as there was no cover near. I would have gone with them until I dropped. Bill said, “You can’t go with us. Why don’t you go out a little ways and lay down.”

The Germans were shooting mostly at the tank. I waited until the machine gun stopped firing for a minute, then I managed to crawl out about 10 feet and lay flat. The machine gunner opened up again. The Germans were in a foxhole and were shooting at the tank from ground level, so the bullets went over me. I looked behind me and could see the machine gun bullets kicking up dirt when they hit the ground. The Germans would stick their weapon out of their foxhole and fire, then duck back down into their foxhole This made it difficult for us to get at them, but our tank was moving in on them. I did not know how bad I was hit, but it was a fight to the death, and I wanted to get my BAR firepower back in the fight. I thought Reynolds, Friedlander, and the others needed the added firepower.

The BAR has two folding legs near the end of the barrel for firing the BAR in the prone position. However, back at Anzio, a piece of shrapnel cut one of the legs off my BAR. The BAR could be fired from the hip, but it weighed about 21 pounds and had a heavy recoil when fired. It was more accurate when the two legs were down, or the barrel was laid on something and fired from the prone position. I dragged myself a few feet over to the power line we had just passed under and laid the barrel of my BAR on one of the small cement blocks that anchored one of the power line pole legs. I was getting weak and cold, and my hands shook, but the barrel of my BAR was pointed toward the German lines, but I didn’t immediately see any Germans.

Our tank was moving forward, and I saw Bill Friedlander fire his M1 rifle toward the Germans. I wanted very much to keep firing my BAR at the Germans, but I was getting weak. I was about to give up firing again, but about 5 seconds after I laid the BAR on the cement block, a German machine gun fired, and the flashes were about where I was pointing my BAR. I squeezed the BAR trigger as hard as I could and held on. The BAR shoots a clip of twenty 30 caliber bullets with every fourth bullet a tracer bullet. The BAR recoil knocked me flat on my back, and I am sure some of my BAR bullets went straight up. I was too weak to fire my BAR again. This all happened in a matter of two or three minutes.

I lay there flat on my back. My side hurt terribly. I was weak and losing blood. I was getting cold. I began to realize that my wound was probably fatal, and I would never see Nettie or Terry again. How would Nettie be able to raise Terry without me? I would not get to see Terry grow up. How would Terry turn out? I loved them and missed them so much. I wanted to go home. I lay in the dirt and wept while my blood was running out, inside me and outside me, and German machine gun bullets were flying over me.

After a while, some of our people came over the ridge, and I called, “Medic, Medic.” I wasn’t able to call very loud, but they saw me. One of them (probably an officer) said, “Where are you hit, soldier?” “In the belly,” I replied. The officer saw me trying to get the cap off my canteen and said, “You should not drink any water.” He turned around and shouted, “Send those medics up here.”

My firing at the Germans had given my position away. The Germans were still firing burst[s] from their machine guns, firing at ground level from their foxhole. When they fired their machine guns, bullets would ping off the metal of the power line pole, but I was laying so flat that they went over my head. I tried again to get the cap off my canteen, but I had become so weak and shaky that I couldn’t get the cap off my water canteen.

Soon a field medic appeared and proceeded to give me a shot in the arm (morphine, I think). It soon calmed and eased me some. While he was giving me the shot, a German machine gun opened up and bullets pinged off the metal of the tower above us. The field medic just tilted his helmet to the side as if he was shielding his head from rain and proceeded to give me the shot. The medic was not hit, but it was a brave act.8 If he had been hit and had not been able to give me the shot, I probably would have gone into a state of shock and died from loss of blood.

While I lay there, I tried to get as much cover from the machine gun bullets as I could from the one-foot wide and four inches high cement block that anchored the power line pole. I found that it was very difficult to get a six-foot body behind a one-foot long cement block. At first, my chest area was behind the cement block. After a while, I thought that my head should be protected behind the block, so I inched down so that my head was behind the cement block. The machine gun was still firing burst at the tower. I felt like my whole body was exposed, and I did not want to get a bullet in the groin area. So I slowly inched my body up to where the cement block was giving some protection to my groin area, and the rest of my body was exposed to the machine gun bullets. Which part of my body was most important to me? My groin area won, but I was not hit again.9

After a while, my dilemma was solved when the medics came up with a jeep, put me on a stretcher across the hood of the jeep, and rode me out of the battle. I learned later that the German machine guns were silenced, and the Americans advanced, but both of my friends, Reynolds and Friedlander, were killed in this battle. Would Reynolds and Friedlander have survived if my BAR firepower hadn’t been knocked out? I will never know, but it will haunt me as long as I live. But I tried to help them. I tried. I tried.10

At the first aid station we came to, the medics took me off the jeep and used a pair of scissors to cut me out of my clothes, and covered me with a blanket. Someone asked me if I had anything in my clothes that I wanted to keep. I replied, “Yes, I want my billfold and my rifle throng case.” The rifle throng case has rifle cleaning supplies, and the M1 rifle that was issued to me at first was a used one and did not have the throng cleaning case that fit in the stock of the M1 rifle. The throng case I had was one I found on the battlefield, and when I had to give up my M1 for the BAR, I kept the throng cleaning case.

I was put in an ambulance, and we stopped at some other aid stations. Once, a member of my squad was in the ambulance with me. He had a bullet through his foot. He said he saw me get hit, and he got hit from the same machine gun burst. He said that the bullet that hit him came under the tank. I don’t remember much other after that, but I think I had an IV in my arm part of the time. I do later remember being carried up some steps, and a nurse said, “We are going to put you to sleep.” I learned later that we were in Mussolini’s bodyguard troops barracks in Rome. The Americans had made a hospital there.

Next: Tomorrow Will Be a Little Easier >>

Footnotes:

- U.S. combat engineers commonly pronounced the word “ponton” rather than “pontoon,” and U.S. military manuals spelled it using a single ‘o.’ The U.S. military differentiated between the bridge itself (“ponton”) and the floats used to provide buoyancy (“pontoon”). ↩︎

- German units began withdrawing to the north of Rome on June 2. ↩︎

- The Roman Colosseum is located about 1km south of the center of Rome. ↩︎

- Declaring it an open city on June 3, the German army left Rome without the destruction that had characterized the evacuation of Naples the previous Fall. ↩︎

- On June 5, the citizens of Rome were in the streets cheering American troops. However, the soldiers who actually liberated the city had already passed through Rome and were again engaging the Germans along a twenty-mile front. Dad was in the force pursuing the Germans. ↩︎

- The Narrative History of the 133rd Infantry places the regiment about 50 miles north of Rome near Civitavecchia. “On 7 June 1944, the regiment moved to the vicinity of Civitavecchia, Italy and the 1st Battalion immediately went into action. The enemy was retreating rapidly, blowing bridges, burning fields and houses in their wake.” Civitavecchia was taken by the 133rd on June 8. ↩︎

- Tedesco (plural Tedeschi) is an Italian word for German. ↩︎

- One of the few WW2 experiences dad readily accounted. He said this was the bravest act he ever witnessed on the front lines. ↩︎

- Dad remarried after mom died in 1992. When hearing this story, his second wife, Doris, quipped “isn’t that just like a man to be more worried about his goober than his head!” ↩︎

- Reynolds would indeed die from wounds sustained in this battle. However, Bill Friedlander survived the war. Unfortunately, Dad never knew Friedlander made it home. ↩︎