June 9 – 21, 1944

Friday, June 9

In the morning, I was awakened by a nurse telling me to wake up as she gently slapped my face. I woke up, but I was weak and had an IV in my arm, a stomach pump in my nose, bandages on my body, and my heart was beating unbelievably fast. I could only breathe in short breaths because the stitches in my stomach hurt, and I could only speak in a whisper. But I remembered my usual morning prayer, which is, “Thank you Lord for keeping me the last 24 hours, and if it be your will, may I have 24 more hours.” I said this prayer to myself each morning while I was in combat, but I never asked for more than 24 hours as it appeared sometimes that He would be hard-pressed to give me 24 hours. And after I was hit and in the hospital, I kept telling myself, “If I can just make it today, tomorrow will be a little easier.” Each day I would tell myself that tomorrow would be a little easier, but it wasn’t easier at first.

One of the bullets went through my stomach, and I had a stomach pump tube down my nose and was instructed to only sip a little water. There was a small glass section in the tubing of the stomach pump, and when I took a sip of water, I could watch, in the glass section, the water return from my stomach. I amused myself several days by occasionally doing this until the pump was removed several days later.

One bullet hit me about 2 or 3 inches below my heart (the bullet hit me one inch to the left and two inches above my navel, and went through my large intestine, my stomach, bottom of my left lung, and out of my back about an inch or two inches from my spine). Other bullets hit my intestines and took out my spleen. I had a drain tube in my back where the upper bullet came out, and two double barrel colostomies in my left side where the other bullets hit. I learned later that some of my intestines were so damaged that a section had to be removed, and the ends were fastened back together with a “Murphy button.” This is what the Doctors called it.1

When I first woke up, my abdomen was in heavy bandages, and since I had felt only one hard smash when I was hit, I thought that I had been hit by only one bullet. It was several weeks later that I was told by a doctor that it appeared that I had been hit by more than one bullet. But then one is seldom hit by one machine gun bullet. The bullet exit wounds in my body appear to have been made by three bullets. My abdomen front is so scarred that I can’t tell where the bullets entered.

My abdomen had bandages on it, but soon I felt a warm liquid under my bandages. This alarmed me as I thought I might be bleeding again, so I called a nurse. The nurse took my bandages off, and this is when I first saw the foot-long wound in my stomach area and the two double barrel (both ends of the severed intestine visible) colostomies where my intestines were exposed. I was embarrassed that my bowels moved out of one of the colostomies, but I had no control over it. But the nurse was very professional, cleaned me up, put a new bandage on, and tied a bow on the bandage. She was very kind.

I had to be cleaned up often, and it was embarrassing, but a few days later when I was stronger and most of the tubes had been removed, I asked the doctor if I could clean myself up and put my bandage on in the latrine. The doctor said I could if I was able, but to call someone if I needed help. I had two open colostomies until I returned to the States several months later. (Both colostomies were closed, one at a time, at McGuire General Hospital in Richmond, Virginia, and I was in the hospital about 13 months. But I was able to come home between operations.) My left side still feels heavy and hurts very bad, but I was able to sleep some most of the day.

Saturday, June 10

“If I can just make it today, tomorrow will be a little easier.”

I am very weak today and had much pain, but I was not hungry. I had IVs in my arm. I slept as much as I could during the day. There was no pain while I was asleep. The nurses changed my bandages when they needed changing. I was still very embarrassed, but the nurses were very professional and kind. When I was awake, I would take a sip of water and watch in the glass tube as it returned from my stomach.

During the night they brought other wounded soldiers in, both German and American. The American in the bed next to me was named Marion. The nurse introduced us. I do not know if Marion was his first or last name. He had a hole in his chest and was very sick. The doctors would draw fluid from his chest every few hours.

A Red Cross worker came by and asked if I wanted him to write a letter for me. I told him that I did, and he proceeded to write down what I told him. The letter was to Nettie, and I told her that I had been wounded, but would be all right. I learned later that Nettie got a report from the government that I had been wounded before she got the letter from me.

I attempted to talk to Marion some, but neither he nor I were able to say more than a few words. Both of us were so weak that we could only talk in a whisper voice.

Sunday, June 11

“If I can just make it today, tomorrow will be a little easier.”

I am still very weak, and can only talk in a whisper. I have much pain in my abdomen. I learned to lay slightly on my left side so fluid could drain out of the drain tube in my left back. I have not eaten anything since I was wounded, but I am not hungry. Marion and I talked a little about where each lived. Each of us was only able to talk in a whisper. If I remember correctly, he was from Iowa.

Our division, [the] 34th Infantry, was originally made up with Iowa National Guard units, and was one of the first divisions sent to England. The 34th saw action in North Africa, Sicily, and southern Italy before I got with them.

Monday, June 12

“If I can just make it today, tomorrow will be a little easier.”

Up in the morning, I noticed that Marion’s bed was empty. When a nurse came by, I asked her where Marion was. I thought he had been moved to another bed or location. The nurse very gently said, “Son, Marion just didn’t make it.” Marion had died. They had given me medicine to make me sleep while they were working with Marion. I wish I could have gotten to know him better. I didn’t even get to know whether Marion was his first or last name.

The doctor came in, examined me, and asked me about any pain. I did have pain, but I was so glad to be alive that I didn’t dare complain. The doctor said I was doing well. I tried to sleep as much as I could. I had IVs and tubes in me, and I had not been given any food, but I was not hungry.

Tuesday, June 12

“If I can just make it today, tomorrow will be a little easier.”

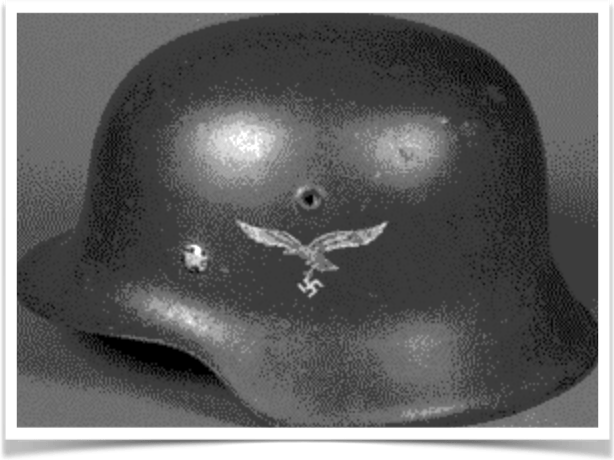

This morning I noticed that there were several new patients in our ward. At each of our beds, there were footlockers with their uniforms folded neatly on them with their helmets laying on the folded uniforms. I soon noticed that some of the new patients were wounded Germans with their uniforms folded neatly on their footlockers with their helmets laying on top. We were all wearing American pajamas.

One wounded German was across the wardroom from me slightly to my right. I had to lay on my right side because of the tubes and colostomies on my left side, so I was constantly looking at the wounded German. The wounded German’s uniform was folded neatly on his footlocker with his German helmet on top of the uniform. The way my bed was placed I had a constant view of the German uniform and helmet. The more I looked at that German helmet, the more I had a terrible urge to shoot that helmet. The wounded German was in American pajamas and looked like us, so I had no urge to shoot him.

“I must kill that German helmet-kill that helmet-kill that helmet.” I lay there all day several days looking at that German helmet thinking of how I could manage to destroy that helmet. I was too weak to move and had tubes in me, but I wanted desperately to kill that helmet. And if I could have gotten a weapon, and was able, I would have blasted it. I had no desire to harm the wounded German soldier in American pajamas. He looked like us. But I had to kill that German helmet. Kill that helmet-Kill THAT HELMET. This lasted for several days until the wounded German and his helmet were moved.

The German helmets had an offset in the edge on both sides, however, the American helmets had smooth edges. So in combat, when we were on night guard duty or night patrol and someone approached us, we looked for the kind of helmet he was wearing. If the helmet had an offset, it was the enemy and we had to kill or be killed. I was later told that I had Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Wednesday, June 13

“If I can just make it today, tomorrow will be a little easier.”

The American medics picked up both American and German wounded from the battlefield, and we were all placed in the same ward room. We were all dressed in American pajamas and looked alike. But you could tell when you saw their uniforms and helmets laying on their footlockers.

Some new wounded were brought in last night, and I noticed that a wounded German was in Marion’s bed next to me. He had a bullet in his upper leg. I tried to ignore him as much as I could, but when the nurses attended him I found that he could speak some English. His footlocker was not in my sight.

I am still weak and haven’t eaten or wanted to eat anything. When the doctor came by, he put on plastic gloves and put his finger in both sides of one of my open colostomies and felt around, and I immediately became sick and vomited. The doctor also felt in my other colostomy. This hurt very bad and I was sick. The doctors did this two or three times each week and each time it made me sick. The nurse that was with the doctors usually brought a vomit pan, and I always used it. They were trying to determine the amount of healing my intestines were doing.

There were magazines available for us to read, Life, Look, and other American magazines. I spent some time looking at these, and I gave a magazine to the German prisoner in the bed next to me. We smiled at each other but didn’t speak.

Thursday, June 14

“If I can just make it today, tomorrow will be a little easier.”

I am still very weak, but I haven’t eaten anything yet. I still have the stomach pump in, and some tubes and IVs in me. I don’t know when they will be taken out. I still have my two colostomies and have to be cleaned up several times each day.

Friday, June 15

“If I can just make it today, tomorrow will be a little easier.”

The doctors came in today and discussed my condition. It was their opinion that I was better, and my stomach pump was to be removed. As the doctor prepared to remove the stomach pump tube that was in my nose, he told me to take a deep breath and hold it. This I did. After a moment the doctor said, “Let it out.” I was about to let it out anyway, so I let it out. After a couple of minutes the doctor said again, “Take a deep breath and let it out slowly,” and he began pulling the stomach tube out through my nose. It was uncomfortable but didn’t hurt much.

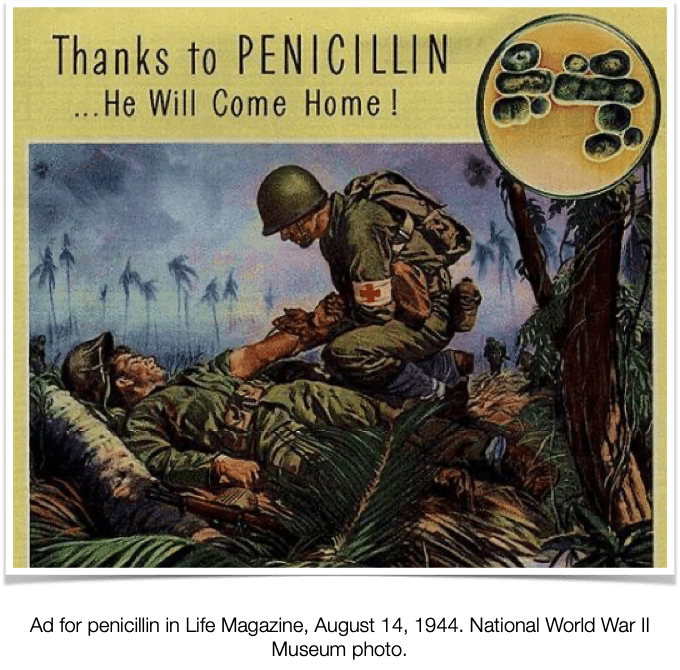

At supper, I was given some soft food. The food tasted good, but I couldn’t each much. I kept it down though. Today the doctors decided that I should be given penicillin. Soon a nurse came in with a needle and gave me a shot of penicillin in the hip. And thereafter I was given a shot of penicillin every four hours day and night. They alternated with the hips, and I soon became sore in both hips. Penicillin was new, and I later was told that they only had a limited supply of penicillin, and would not give it to a dying soldier. Only when a soldier showed signs of living was he given penicillin.2

Saturday, June 16

“If I can make it today, tomorrow will be a little easier.”

At breakfast today, they brought me a tray of liquid and soft food. I am not hungry, but I ate some food. I am very weak, and I realized that I needed to eat and try to gain some strength back. But about 9 am, the doctors came around. One of them put on rubber gloves and put his finger in each of my colostomies to see if they were healing up. I immediately became sick and vomited up my breakfast. At lunch, they brought some more liquid and soft food, and I ate some of that food and kept it down. I spent most of the day sleeping and looking at some magazines. But I still wanted to shoot the German helmet that was on the footlocker across from me.

I tried to talk to the German prisoner in the bed next to me but with little success. He did not seem to want to talk. But we did exchange magazines.

I am getting some stronger, and this afternoon several of the American patients gathered around my bed and discussed politics. This is an election year, and President Roosevelt is being challenged by a Republican named Windell Wilkie [Wendell Willkie]. And of course, there were some American soldiers that were for each candidate. The German prisoner in the bed next to me could speak some English. He said he learned English in the German school system. When in the discussion some of our soldiers said they didn’t like President Roosevelt, his eyes got big like he couldn’t believe it. One of the American soldiers asked the German prisoner what would happen in Germany if German soldiers spoke about Hitler like American soldiers spoke about Roosevelt. The wounded German prisoner said, “In Germany if a soldier or anyone spoke negatively about Hitler, he would be shot.” It was obvious that the German prisoner did not know what a free election was.

Sunday, June 17

This morning the doctors said I was well enough to be moved to a general hospital along with several other patients, and we will be moved out tomorrow morning. The general hospital we were going to was in Naples.

During the day, the doctors removed all the tubes in my body that had to be removed so I could be moved. There was a drain tube in my back where a bullet came through, and the drain tube had to be removed. When they came to remove the tube, the doctor looked at my back and told me to lay on my stomach. The doctor said, “Take a deep breath and hold it.” I did, and after a few seconds he said, “Let it out.” I thought for a moment or two that the doctors had changed their minds. But soon the doctor said again for me to take a deep breath and hold it. And wham! The doctor had jerked the drain tube out of my back, and it felt like all my insides came with it. The hole bled pretty bad, but they put a bandage on it and let me sit up.

Monday, June 18

After breakfast, they loaded us on trucks and headed to the Rome train station. Most of us were very weak, but they were kind to us and helped us that needed help. Some were on stretchers and had to be carried. I did not need a stretcher, but I had to have some help. After a short ride, we appeared at the Rome train station, and they helped us get off the trucks and to get on the train.

We were told that this was the first train to leave Rome since the Germans left. Many of the rails in the railyard were twisted and broken, but they had found enough straight rails for our train to head south. I was told that American bombs did most of the damage to the railyard while the Germans were still there.

I looked at the Rome buildings as we left to see if I could remember any I saw as wecame into Rome. I looked for the old coliseum [Colosseum] ruins that we passed as we come into Rome. I did not recognize any of the buildings, and I was not able to read any of the street signs.

In the afternoon, the train came near some mountains with the mouth of several caves visible in the mountainsides. We were told that these were the caves where, in earlier times, Christian prisoners were kept. I wondered if one of these caves was where the Apostle Paul was kept prisoner when he was in Rome.

The train moved slow, and we slept on the train this night.

Tuesday, June 19

After breakfast, as we approached Naples, we could see Mt. Vesuvius in the distance. It was erupting, and the mountain appeared to be on fire, but we saw mostly smoke. In Naples, I saw that most of the buildings were mostly made of brick, and many had balconies. The train stopped near one of the larger buildings, and we were helped off the train and into one of the larger buildings. The Americans had made a convalescent hospital there.3 I was assigned to a large room with several other wounded soldiers. Our building had a balcony, and we had a good view of Mount Vesuvius. In the daytime, the mountain had some fire visible, but it was mostly smoke. At night it looked like the mountain was on fire.

Wednesday, June 20

We were treated good here, but we did not know if we were going home or back to the fighting when we got better. I still have two double barrel colostomies, and my bowels move out of one of the colostomies. The doctors would put their gloved finger in each of my colostomies two or three times each week. The doctors wanted to see if I was healing up alright, but it made me sick each time. They knew that I would be sick, so a nurse would bring me a pan to vomit in. I had no control over my bowels, but I cleaned myself up in the latrine each time and put new bandages on. I had to go to the nurses’ desk to get the bandages. The boys I talked to did not think I would be able to go to the front anymore.

Thursday, June 21

These days I spent reading magazines, looking at Mt. Vesuvius from the balcony, or playing twenty-one (a card game) with the other wounded boys. We used pennies mostly, but if one didn’t have a penny he could put in a match or any small item that he had. The idea was to stay busy, not to gamble.

I never got paid while I was overseas.

Footnotes:

- The Murphy Button is a device consisting of two button-like hollow cylinders, used for intestinal anastomosis (or cross connection). Each cylinder is sutured to an open end of the intestine, and the ends are fitted together. ↩︎

- At the beginning of 1941, penicillin was barely out of research. After joining the war in December 1941, the U.S. government took over the research and production of penicillin, mobilizing government agencies, research labs, universities, and pharmaceutical companies to produce penicillin in bulk. ↩︎

- This may have been the 17th General Hospital. The hospital is known today as the Antonio Cardarelli Hospital, and is said to have great balcony views of Mt. Vesuvius. ↩︎